Some people are their own worst enemy. And that old saying also applies to financial institutions.

With all the talk about revisiting, gutting or eliminating Dodd-Frank, a significant part of the problem with mortgage appraisal related lending actually exists within the bank risk management themselves. Their over-interpretation of what the regulations require gives outsiders the impression that appraiser related regulations or standards are more onerous than they actually are.

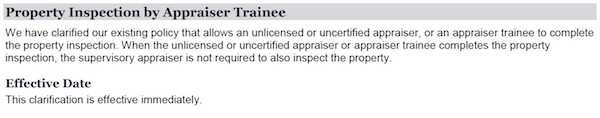

Fannie Mae Allows Trainee Inspections Without Their Supervisory Appraiser

One of the biggest issues today is the lack of mentoring by experienced appraisers because it is not financially feasible under current lending practice. Both banks and AMCs – who act as a bank’s agent – generally do not allow trainees to inspect a property without a licensed or certified appraiser alongside. So in an era where AMCs control as much as 90% of mortgage appraisal work, the lenders are requiring AMCs to require something the GSEs (the party buy their mortgage paper) do not require. This risk aversion is residual from housing bubble collapse. Mortgage lenders today, subjected to low rates and a very narrow rate spread, remain irrationally averse to risk.

However, their underwriting risk management is effectively destroying the future quality of appraisals that will be done on their collateral because the new wave of appraisers is essentially only book-smart without real world context (mentoring). Experienced appraisers can not afford to invest the time to inspect the property with the trainee (in addition to their own inspections) for the multi-year experience period before the appraiser is certified after already taking a 30% to 50% overnight pay cut from AMCs.

From the Fannie Mae Seller’s Guide Update – 2017-01 page 2.

Reporting “Material Failures” to State Boards

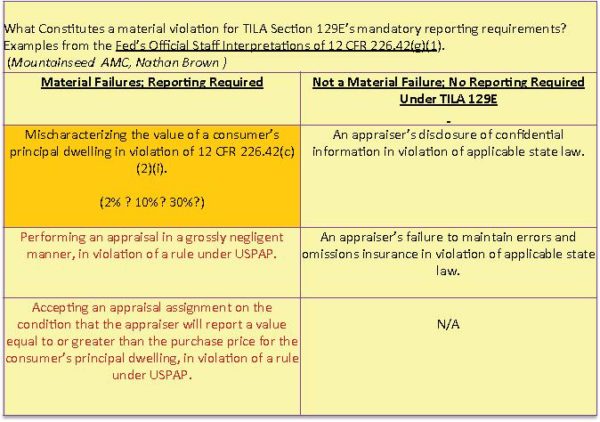

In reference to appraisal oversight, let’s consider how banks determine whether an appraiser is reported to their state licensing board.

Dodd-Frank says the following in 12 CFR 226.42(g)(1). Whereby a lender has to report an appraiser for…[bold, my emphasis]

(g) Mandatory reporting—(1) Reporting required. Any covered person that reasonably believes an appraiser has not complied with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice or ethical or professional requirements for appraisers under applicable state or federal statutes or regulations shall refer the matter to the appropriate state agency if the failure to comply is material. For purposes of this paragraph (g)(1), a failure to comply is material if it is likely to significantly affect the value assigned to the consumer’s principal dwelling.

When the CFPB was asked what they meant by a “material failure” – the following table shows the difference between material and non-material. So how much is a material failure? A value off by 2%, 10% or 30%?

And by the way, the third option for reporting a material failure seems absurd although I suppose it has to be said – Who is dumb enough to admit that they accepted the assignment because they knew they would “make the deal” happen. The obvious lack of a definitive paper trail in such a situation makes this very hard to prove.

I’ve always had a problem with setting rigid rules in considering the concept of appraisal oversight. With valuation expertise, how does a state agency apply hard rules to value opinions, comp selection and adjustments, etc.? There needs to be a great deal of latitude for regulators and an “I’ll know it when I see it” approach should be allowed.

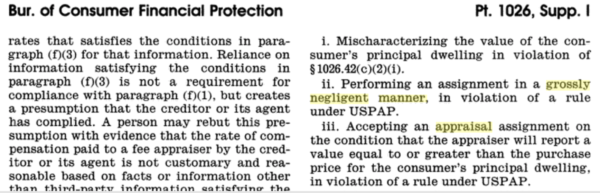

Separating gross negligence from negligence

Here is the rule.

“Performing an appraisal in a grossly negligent manner, in violation of a rule under USPAP.”

While subjective, it represents a very severe extreme to which an appraisal would be reported to a state board. The rule goes on to say…

“Accepting an appraisal assignment on the condition that the appraiser will report a value equal to or greater than the purchase price for the consumer’s principal dwelling, is in violation of a rule under USPAP.”

But big national mortgage companies today like Wells Fargo and others are reporting appraisals to state boards where the value is not supported. ie weak comps, unreasonable adjustments, etc. Reports with those issues may, in fact, be negligent but do not fall under the definition of gross negligence. Let’s not wreck an appraisers career because they missed some better comps. Once these reports are referred to the state, the state must investigate. It opens up the appraiser to more risk of unintended consequences. Think of a scenario where a cop pulls over a driver for a missing taillight and learns that the driver doesn’t have his wallet with him.

Gross negligence requires a much higher test than applying it to an appraiser who is just being stupid.

It is defined as:

Gross negligence is a conscious and voluntary disregard of the need to use reasonable care, which is likely to cause foreseeable grave injury or harm to persons, property, or both. It is conduct that is extreme when compared with ordinary Negligence, which is a mere failure to exercise reasonable care.